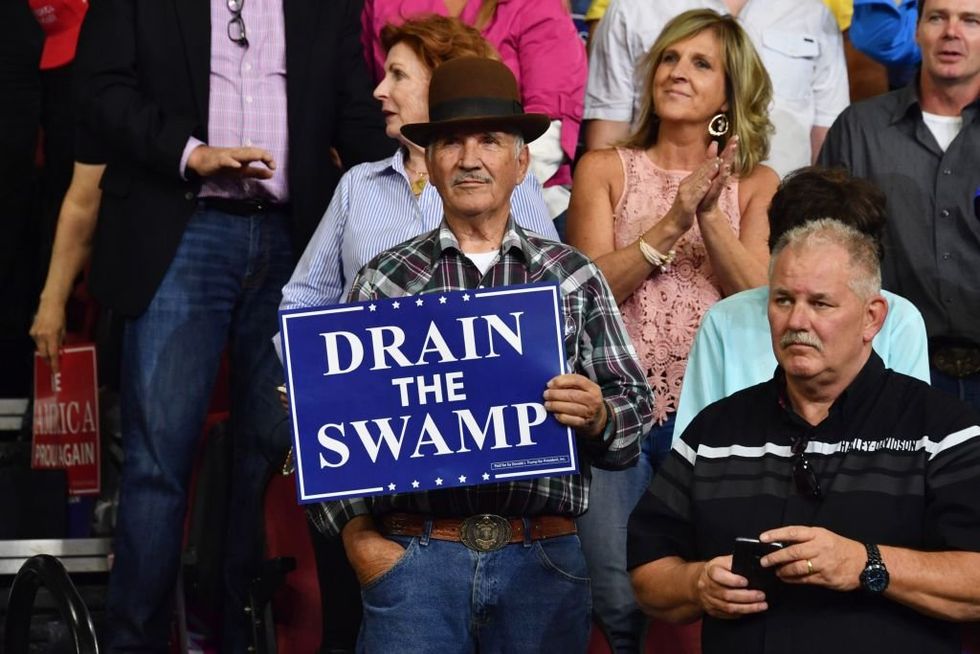

One way to drain the swamp: Start with transparency

Draining the swamp requires hard work. You can’t do it casually or haphazardly. The bureaucracy has spent more than 125 years building the administrative state, and it won’t go quietly.

During President Trump’s first term, we learned that bureaucrats holding power have largely insulated themselves from the electorate and elected officials. Long-term structural change will need legislative reform, starting with the Administrative Procedure Act, the key law governing the relationship between Congress, agencies, and the courts.

A regulation can only change the rational thinking of those who know and understand it. Yet we are all subject to countless regulations we neither know nor understand.

Executive action will only have a lasting impact if it’s taken consistently and coherently. Railing for a return to the pre-progressive era of William McKinley serves no purpose. Modern life is complex and interconnected. The trust and sense of community that once stabilized interactions between neighbors are inadequate in today’s world of global supply chains, faceless corporations, and weakened communities. While the administrative state can be reduced, it can’t be eliminated.

Reform must start with a simple, clear, and explainable theory of regulation, then adjust the massive regulatory code accordingly. Fortunately, such a theory exists, and leading bureaucrats have already adopted it. Recent high-profile actions by bureaucrats also provide clues for reform. The key is to use these insights strategically.

Barack Obama’s regulatory czar, University of Chicago law professor Cass Sunstein, popularized the essential theory: Regulations “nudge” people toward making socially desirable decisions. Merrick Garland’s Justice Department and several big-city district attorneys have shown the key reform tool: enforcement discretion. When used effectively, this combination can achieve more swamp draining in one presidential term than has occurred since the New Deal.

Start with the theory of regulation — or, more broadly, of law. The basic premise, drawn from economics, is that people generally make rational decisions. In other words, when facing multiple options, I will choose the one I believe provides the greatest benefit to me. But if society decides that my self-serving choice imposes unacceptable costs on others, a regulation can change my decision-making by making that option more expensive, perhaps through criminal penalties or civil fines. Regulatory subsidies favoring “more socially desirable” options can have the same effect.

Take, for example, a manufacturing company choosing between two industrial processes: Process A costs $80 per unit but adds $40 in pollution costs. Process B costs $100 per unit with no pollution. Without regulation, a rational company would choose process A and leave taxpayers to pay for cleanup. A regulation that forces the company to clean up its own pollution changes this calculation. The company would likely spend the extra $20 for process B, save taxpayers from footing the bill, and generate an overall societal saving of $20. This is an example of an environmental regulation worth preserving.

Essential executive action

During the Obama years, Sunstein and his fellow progressives used this theory to encourage progressive behavior. We can improve on this approach by reversing the script. Instead of starting with the behavior we want to promote, real reform must begin from the decision-maker’s perspective.

A regulation can only change the rational thinking of those who know and understand it. Yet we are all subject to countless regulations we neither know nor understand.

One of the great tragedies of modern life is that we face so many rules, on so many topics, that we have no idea what’s expected of us. Who among us could withstand the scrutiny of a special prosecutor? If the government randomly subjected Americans to such investigations, nearly anyone could be incarcerated or ruined. Besides the obvious violation of civil liberties, this situation points to a larger regulatory failure. If a successful regulation redirects behavior toward socially beneficial actions, then any unknown or poorly understood regulation fails by default.

Enforcement discretion can have a similar effect. When a district attorney announces that she won’t prosecute shoplifting, for example, it effectively nullifies theft laws. Those of us with a basic moral code may still pay for the items we take because it’s the right thing to do. However, those with a weaker moral compass may revise their thinking and conclude that simply taking what they want best serves their (at least short-term) interests.

Draining the swamp requires aligning enforcement discretion with the theory of regulation: Only enforce regulations that people know and understand. How can an agency determine which of its regulations are known and understood? That’s where executive action comes in. An executive order can direct agencies to explain their regulations before enforcing them.

Consider an announcement and order along the following lines:

The purpose of regulation is to encourage behavior that benefits local communities and the nation. But many Americans, both individuals and corporations, don’t know which laws apply to them or how the law expects them to behave. These laws can’t promote the behavior they claim to encourage; instead, they act as “gotchas” that allow enforcement agencies to punish innocent Americans who didn’t know they were doing anything wrong.

We are giving every agency 90 days to review everything within its enforcement jurisdiction. For each regulation, the agency must publish a simple statement explaining whom the regulation affects and the behavior it aims to deter or promote.

These new explanations are not legal statements. They describe enforcement discretion. Moving forward, agencies will only enforce regulations against those they have informed, in line with the behaviors they have identified. No agency will bring a new enforcement action under any regulation unless it has been publicly explained and available for at least 30 days.

That’s it. Officially, this approach doesn’t eliminate any regulations or change the scope of agency power. Practically, it disciplines all agency actions. It requires our government to tell people how we expect them to behave, promoting both government transparency and socially beneficial behavior.

This approach also reduces the need for expensive compliance professionals and replaces technical, legalistic disclosure with real disclosure — placing necessary information front and center, rather than hiding it in a footnote that only a legal team would notice.

Redirect the flows

Entire swaths of the federal government and the compliance and lobbying industries would suddenly lose power. Opposition would be fierce, but difficult to justify. Opponents would be left arguing against fair notice and warning before enforcement. Even better, this approach would shift the balance of power in the swamp. Bureaucrats have grown so powerful because the regulatory code is both sprawling and opaque. Enforced clarity would strip them of one of the biggest weapons in their arsenal.

Long-term benefits are also likely. By forcing agencies to choose between clarifying their authority or ceasing to use it, such an order would force them to prioritize. Presumably, each agency would clarify the regulations it most wants to enforce first. Low-priority regulations left unenforced for extended periods would become increasingly hard to defend. A collection of these long-unenforced regulations would make an excellent case for an omnibus deregulation bill. A significant reduction in the regulatory code, in turn, would justify a corresponding reduction in the federal workforce.

Restructuring the federal government is tough work. Progressives aimed to do it in the 1890s under William Jennings Bryan and in the 1910s under Woodrow Wilson. However, they saw only marginal success until the 1930s. Faced with a true crisis and a theory of the administrative state, FDR fundamentally changed the American system of governance.

We’ve reached another crisis point. Regulatory sprawl and vast enforcement discretion have undermined every remaining republican virtue. No living American can possibly understand the entire regulatory code, which means everyone is arguably in violation of something. This vast enforcement discretion allows the government to target and harass anyone deemed objectionable for any reason. Constitutional norms that haven’t yet been discarded are under constant threat.

The only way to rein in the bureaucracy and restore republicanism is with a coherent theory of regulation and a realignment of enforcement discretion. I’ve presented a plan that’s simple to explain and easy to sell. Maybe there are other options.

Ultimately, the only way to drain a swamp is to redirect the flows that feed it. Opaqueness and discretion are two of the main feeders. Redirect them, and we can reclaim the American constitutional order.