Jesus Christ’s cross-shaped strength resists muscular Christianity

Jesus’ triumph over the powers of darkness is one of the great doctrines of the Christian faith. As a Christian, I take great confidence and comfort in his conquest. Sin and death no longer hold power over me because of the devastating victory secured over them by Jesus. Every time we proclaim that Jesus is Lord and Christ is King, we are reminded that “he disarmed the rulers and authorities and put them to open shame, by triumphing over them in him” (Colossians 2:15, ESV).

Yet there is an emerging attachment to Christus Victor that looks far more like Nietzsche than Christ, to the extent that I wonder if we’re talking about the same Jesus.

The victory of Jesus, to these folks, is permissive rather than formative; it is a call to aggression rather than cruciformity. This shift is taking place most clearly in the Christian nationalist circles, where the evidence is regular, if you’re looking for it.

What’s the big deal?

Let’s back up. What’s the problem? After all, none of us are keen on losing. None of us want to be made to look the fool. Being a Christian in the open isn’t what it used to be. With secularism in the cards, the deck is stacked against Christians in the public square.

Every time we try to make Jesus more explicable, we make him smaller. And in his grace, he just won’t let us do that.

Isn’t growing a spine a good thing? Shouldn’t we be celebrating Christian strength in an antagonistic world?

Sure. Maybe. Well, it depends.

The Gospels are filled with people trying to make sense of Jesus by categorizing or locating Jesus in their religious-political-cultural schema. And they’re littered with the wreckage of their failed attempts, as Jesus deftly explodes each one. Don’t take my word for it; see Matthew 16:32; 19:10, 13; Mark 6:52; 10:26; Luke 9:54; 18:34; John 4:27.

It seems we’re still struggling to make sense of him today.

Why? Because Jesus is punk rock and doesn’t like to be labeled? No. Because he’s God, and every time we try to make Jesus more explicable, we make him smaller. And in his grace, he just won’t let us do that.

A muscular Jesus for a muscular Christianity

It seems to me that many people, particularly the Christian nationalists and many on the far right, want a more muscular Jesus for a more muscular Christianity. Tired of a weak religion, these folks crave something more vibrant, more directed. And really, I don’t begrudge the effort. We still haven’t figured out what to do with modernity. And we certainly haven’t figured out what to do with men and masculinity in a modern world. Many Christians are hungry for someone, anyone, who can point them toward a meaningful vision of constructive and creative strength.

As Christians, we know we should point them to Jesus. But perhaps Jesus has a bit of a PR problem? Is it really a good idea to tell your constituents not only to take one on the chin but to willingly offer the other side? And then to go model it by getting crucified? The last thing we need in our masculinity crisis is a teacher who tells men to become more meek and make peace a priority. And then there’s that deeply problematic episode where Jesus does the slave work of foot-washing and then tells his elite crew to follow suit.

Perhaps, then, we need to rehabilitate Jesus’ image — to give him a slightly tougher edge, a bit more grit, maybe some red laser eyes. With the revisionist’s flair, we recut this film to include the scene where Jesus flips temple tables while wielding a whip, then cut to the one where he stills a storm with a single word and finally to the exquisite takedowns: “whitewashed tombs,” “children of hell,” “brood of vipers.”

This seems to be the thrust of a recent article that invokes Nietzsche to frame the pitiful state of contemporary evangelicalism. While admitting that he doesn’t agree with Nietzsche’s conclusions about Christianity (I should hope), the author argues that the American church has become a “pacified church obsessed with soothing our pitiful state.” What we need, he argues, is an invigorated passion for virtue, honor, and “manly warfare.” Or to put it differently, we need a muscular Jesus for a muscular Christianity.

Seeing Jesus rightly

The problem — as you’ll have anticipated by this point — is that in doing this, we’re not really pointing people to Jesus but to a magazine-cutout collage of what we desire Jesus to be.

Jesus spends so much time exploding malformed notions of himself because sin has twisted our understanding of what humanity is supposed to be. The experience of redemption is not simply about escaping the penalty for our sin but about being remade, or reformed, into humanity as God intended.

This is why Paul tells us that we’ve been predestined to be conformed to the image of his Son (Rom. 8:29). Through sin, we’ve lost the plot on what it means to be human. In Jesus, we rediscover it.

True greatness is found in humble service. That true triumph is had through suffering. And that true power is gained through weakness.

Which means we have got to see Jesus as he presents himself. The whole Jesus, the complex and three-dimensional Jesus.

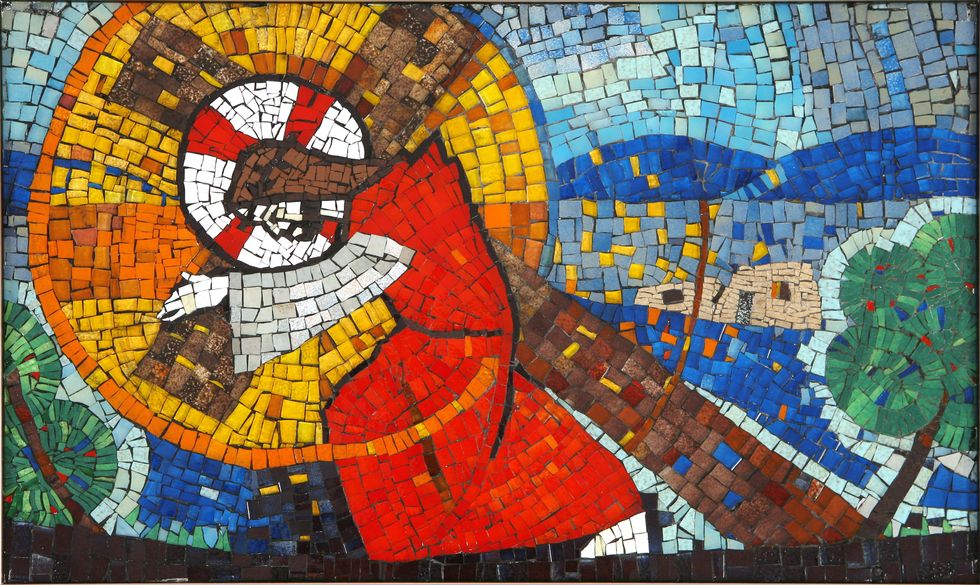

We must hold together what feels like tension to us: the King riding into Jerusalem with the abused and crucified Christ; the sharp-tongued destroyer of hypocrisy with the King who welcomes wild little children; the all-knowing man who would not entrust himself to humanity with the suffering servant who asks his friends to stay up while he prays in agony; the mighty stiller of storms with the healer who has compassion on the relentless, crushing masses bringing their most vulnerable to him.

Or perhaps the vision in Revelation 5 puts it best: “‘Weep no more; behold, the Lion of the tribe of Judah, the Root of David, has conquered, so that he can open the scroll and its seven seals.’ And between the throne and the four living creatures and among the elders I saw a Lamb standing, as though it had been slain” (Revelation 5:5-6, ESV).

The conquest of the Lion is effected only in the sacrifice of the Lamb. And so they remain, indivisibly bound together.

I’m convinced that Nietzsche grasped the true outlines of the gospel. He understood what it meant for God the Son to die for the sins of the world. But he hated that vision. He was disgusted by the weakness and apparent inconsistency of it all. He wanted a vision of strength — a self-sufficient humanity that took the chaos of the world by the horns and made something glorious out of it.

It seems he’s finding company once more.

But Nietzsche missed the real beauty of the gospel. My hope is that Christians trying to find their footing in this tumultuous world won’t, that they will instead see that true greatness is found in humble service. That true triumph is had through suffering. And that true power is gained through weakness.