Can John Ratcliffe tame the deep-state beast at the CIA?

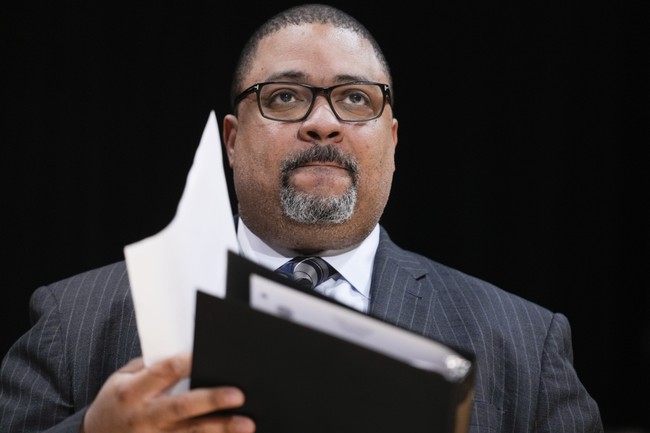

Donald Trump has selected John Ratcliffe to lead the Central Intelligence Agency. Ratcliffe’s experience as a member of Congress overseeing the intelligence community and later as director of national intelligence highlighted his readiness to confront the CIA’s abuses of power during the Russia investigation. However, leading the CIA requires more than a strong director; it demands a capable team to implement meaningful reforms.

Drawing on my 19 years of service in the CIA under four presidents and eight directors, I offer insights into how the next director can navigate and reform the entrenched bureaucratic structures often called the “deep state.”

The goal should not be merely to dismantle the deep state but to establish an environment where transparency, accountability, and integrity are the new norms.

History shows that even the most skilled directors can become figureheads without solid backing. When John A. McCone succeeded Allen Dulles in the 1960s, Dulles’ personnel retained control of the agency, keeping McCone in the dark about key activities. More recently, John Brennan’s influence persisted within the CIA under Mike Pompeo’s leadership. Gina Haspel, who served as Pompeo’s deputy and later as director, continued Brennan’s legacy through his surrogates. Brennan had handpicked and groomed Haspel, who reportedly played a key role in assembling the Steele dossier.

To effect real change, the new director must secure organizational support, beginning with the deputy director. The deputy director will play a critical role in complementing Ratcliffe’s vision and overcoming bureaucratic inertia. This position must focus on managing the agency’s operations effectively rather than allowing career civil servants to dictate their will to the director. Appointing the right deputy director is essential for achieving meaningful reform.

Many people don’t realize how much of the CIA director and deputy director’s time is consumed by protocol duties. They manage communications and meetings with foreign dignitaries and advise the president and key administration officials on complex intelligence issues. As a result, career CIA staff — sometimes called the “Defenders of the Bureaucracy” — often handle much of the operational management.

This makes the role of chief operating officer, the agency’s No. 3 official, particularly vital. The COO oversees daily operations and serves as the critical link between the CIA’s leadership and its operational staff. A COO aligned with the director’s goals can dramatically improve the director’s ability to implement policy changes. The new director must ensure that the COO and deputy director manage the agency in line with the director’s reforms, rather than allowing career bureaucrats to control the COO, deputy, and director, as was the case with McCone and Pompeo.

Other key appointments include stakeholders often overlooked, such as the heads of the Office of Congressional Affairs and the Office of Public Affairs. Congressional Affairs plays a critical role in shaping perceptions and securing support in Congress. Without a trusted ally here, bureaucrats could undermine the director’s agenda through legislative channels. Similarly, the Office of Public Affairs influences public and media narratives about the CIA. Exercising control over this office can prevent leaks intended to discredit or pressure the director into serving bureaucratic interests rather than pursuing meaningful reform.

And we must not forget the Office of General Counsel. Past abuses in this office, especially in handling personnel and whistleblower issues, highlight the urgent need for legal alignment with the director’s reforms. The OGC’s litigation division has been a stalwart defender of the bureaucracy, seeking to crush whistleblowers, making it nearly impossible to foster an agency culture of accountability that aims to stop abuses of power.

The task at hand is immense. The CIA’s internal culture and the broader intelligence community’s dynamics resist change. History offers cautionary tales, such as the tenure of former Director Porter Goss, who faced intense internal opposition. His efforts to implement reforms were undermined by leaks that ultimately embarrassed his leadership and curtailed his time in office. Any incoming director must know that he could suffer the same fate as the entrenched career bureaucrats who will resist change.

As Ratcliffe or any successor assumes the director’s office, he must be prepared for a battle against the internal saboteurs and the inertia and resistance within. The support system around a new director will determine his success in leading the CIA and truly reforming it. The goal should not be merely to dismantle the deep state but to establish an environment where transparency, accountability, and integrity are the new norms, ensuring that the agency serves its true purpose of safeguarding national security without overstepping its bounds.

Ratcliffe faces a daunting journey that will test his resolve like never before. However, with the right team and strategy, he has the potential to redefine CIA leadership in the 21st century. By fostering a culture of accountability and transparency, Ratcliffe can help the CIA return to its original purpose, free from abuses of power and bureaucratic overreach.